This page contains resources on “The Art of Doing a PhD” – or in other words different good advice for surviving graduate school. The page is constantly under construction and I will continuously add stuff here.

I made a presentation on the subject at the Doctoral Colloquium at the UbiComp 2007 Conference:

A newer version of “The Art of Doing a PhD” presentation is available below together with a presentation on how to write a paper:

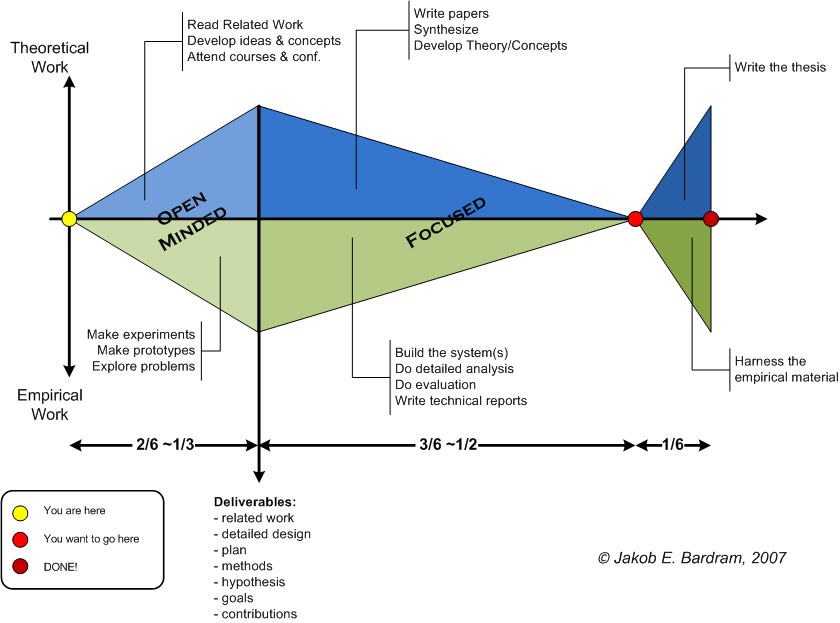

The Fish Model

I often use the ‘fish model’ depicted below when I need to explain to prospective and current PhD students what the flow of a PhD looks like. I still need to explain it here, but the presentation above provides detailed descriptions.

The 3 Core Research Skills – Simple Guidelines

Here is a set of simple guidelines for (i) giving your PhD talk, (ii) writing a paper, and (iii) reviewing a paper. The three core skills in research. If you master these, you’re a researcher!

PhD Talk Outline

You should always have your PhD talk ready – you never know when you need it; when your uncle at the dinner table asks; “what is it exactly you’re doing?” Or when you meet the most famous professor in your field in the elevator (the so-called elevator pitch). You should have 3-4 versions of your PhD talk:

- 1 min – This is the elevator pitch, which you can say by heart without any slides, demo, or anything

- 5 min – This is the slightly longer version where you can tell or show a bit more about what your PhD is focusing on. Exists both with and without slides.

- 20 min – This it the full talk that you give when you visit another lab or at a conference (e.g. at a doctoral colloquium). This is with slides and preferably a demo.

The outline of a PhD talk is (no matter the length):

- Background – what is the community, problem, and motivation

- Prior work – what is the state of the art and what research/technologies / studies exists

- Gab – the “however” sentence; what is missing, what is your research statement/question

- What – the “therefore” sentence: what you (plan to) do

- Methods & Plans – how will (did) you do this?

- Contribution – reflecting back to the background and introduction, what does your research contribute to the overall research question and community

Finally, if you built things (hardware, software, design probes, etc.) you should always be able to demo your research – as they say at MIT;

“DEMO or DIE!”

Paper Abstract & Introduction Outline

Almost all papers use the same template for a (good) abstract and introduction, as outlined below:

- Background – Introduce the background of the paper, including the topic and application area of the paper. Also, include a small summary of prior work done in this area. The background section should include sufficient information, for the reader to acknowledge your “however” statement, coming up next.

- However, gap – This is the MOST important part. By taking an offset from the background section, explain precisely what is missing or what problem you are addressing in this paper. Note that you can only have one “however” sentence in your paper – one paper deals with one problem at a time.

- What we did – Describe in more detail what you have done to solve the problem just stated, including what methods you applied and what results you obtained.

- Contribution(s) – Clearly outline the specific contributions of this paper, as related to solving the problem stated.

- What it means – Discuss how the contributions of this paper relate to the background introduced initially. Did you solve the problem is a greater context and what are the implications of this for the topic or domain you are addressing?

Paper Review Guideline

As a PhD student, you will be asked to peer-review papers. At first, you might consider this a time-consuming and non-productive task. However, there are several reasons why this is an important task to spend time on. First, refereeing (reviewing other papers) is an excellent opportunity for learning what makes a good (and bad!) paper. Second, it is an important avenue for being a part of a scientific community, which is the network you will need in your future career. Finally, in all fairness, all the papers you submit will typically be reviewed by three reviewers. Hence simple math tells you, that you need to review three times the papers you submit.

Below is a general outline of how to write a paper review. It works (more or less) for both conference and journal papers:

- Summary – Briefly summarise the paper in 2-3 sentences (if you can’t, there is probably something wrong with the paper).

- Motivation & Relevance – How relevant is the work to the expected readers, i.e., the scientific community the paper is submitted to? How well motivated is the research? How well-defined is the research problem? Is this a problem that this community cares about?

- Past / Related work – Does the paper outline prior work and explain the state of the art? Is all prior work covered or is there something missing? Is the presentation of prior work fair and correct?

- Contribution – What is the scientific contribution (i.e., novelty) of the paper over prior work? Note that a contribution can take many forms, but the authors should be able to point out precisely what their (intended) contribution is.

- Significance – How important is this work as compared to both the stated problem/motivation but also more general? Will this be something that will be important in 5 years from now?

- Validity & Quality – Is the research valid and have appropriate methods been applied? What is the quality of the research in terms of the size of the study, covered cases, and execution of the research?

- Originality – How original is this research? Ground-breaking or a small increment to existing research?

- Quality of writing – Is the message clear? is the paper well organized easy to follow and understand? Is its style exciting or boring? is there a good flow of logic/argumentation? Is it grammatically correct? are figures and tables used well and integrated into the text?

The following resources are very useful:

- The ACM CHI 2024 Guide to Reviewing Papers. This page describes in detail how to review papers for CHI. It is applicable to most ACM venues, including other SIGCHI conferences and ACM IMWUT.

- I (also) highly recommend Ken Hinckley’s thoughtful piece on what excellent reviewing is.

- Saul Greenberg has done some notes and a presentation on “How To Referee“.

Scientific Contribution

The core of doing a PhD is to make (at least) one scientific contribution. In order to do so, you need to;

- know existing (prior) scientific work so you can argue how your work is a novel contribution

- come up with a new thing – a theory, a concept, a technology, an application, a study, etc.

- document it in scientific publication(s)

What is a contribution, then? This can basically come down to asking if what you have done (or are planning to do) is;

- novel – have you come up with something that is novel compared to prior research?

- significant – have you solved a relevant and non-trivial problem that has a significant impact on the world?

- valid – have you used appropriate methods in your research in terms of data collection, analysis, technology building, etc.?

Jacob O. Wobbrock has written a nice document on different types of contributions. Even though this is written within a Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) perspective and uses examples from the HCI literature, the types are actually pretty generic and apply to computer science more broadly. The types are:

- Empirical research contributions consist of new findings based on systematically observed data. Empirical contributions may be quantitative or qualitative (or mixed) and usually follow from scientific studies of various kinds (e.g., laboratory, field, pilot, deployment, etc.).

- Artifacts are inventions, including new systems, architectures, tools, techniques, or designs that reveal new opportunities, enable new outcomes, facilitate new insights or explorations, or impel us to consider new possible futures.

- Methodological research contributions add or refine the methods by which researchers or practitioners carry out their work. Research methods enable scientists to make new discoveries, while practitioner methods enable designers and developers to apply their craft to greater effect.

- Theoretical contributions consist of new models, principles, concepts, frameworks, or important variations on those that already exist. These may be quantitative or qualitative in nature but are always structured so as to be useful in the pursuit of future knowledge.

- Datasets contributions provide a new and useful corpus, often accompanied by an analysis of its characteristics, for the benefit of the research community. Datasets enable evaluations against shared benchmarks by new algorithms or systems.

- Survey contributions are attempts to review and synthesize work done in a research field with the goal of exposing trends, themes, and gaps in the literature. Survey contributions take a step back, organizing the literature of a field and reflecting on what it means.

- Opinion contributions seek to change the minds of readers through persuasion. Although the term “opinion” might suggest a less-than-scientific effort, in fact, opinion contributions, to be persuasive, often draw upon any or all of the above contribution types to advance their case.

Resources

- Saul Greenberg’s Grad Tips

- “So long, and thanks for the Ph.D.!”. A.k.a “Everything I wanted to know about C.S. graduate school at the beginning but didn’t learn until later”, Ronald T. Azuma, UNC, 1997, 2003

- Research Contribution Types in Human-Computer Interaction by Jacob O. Wobbrock, The Information School University of Washington.

- The PhD Comics site.

- Jason Hong at CMU has an extensive list of resources on his Grad School Advice page. I highly recommend looking at this.

- Research Patterns by Dan Olson (2003).

- How to Write a Great Research Paper by Simon Peyton Jones, MS Research Cambridge.

- How to write Research Articles in Computer Science and Related Engineering Diciplines by Ivan Stojmenovic, Electrical, Electronic and Computer Engineering, University of Birmingham, UK

- The ITU Survival Guide to Living in Copenhagen

Other PhD Thesis’s for Inspiration

- Context Management and Personalisation: A Tool Suite for Context- and User-Aware Computing by Andreas Zimmermann.

- DEMAIS: A Behavior-Sketching Tool for Early Multimedia Design by Brian Bailey, University of Minnesota.